Elizabethan Interior Decoration

A (very) brief history

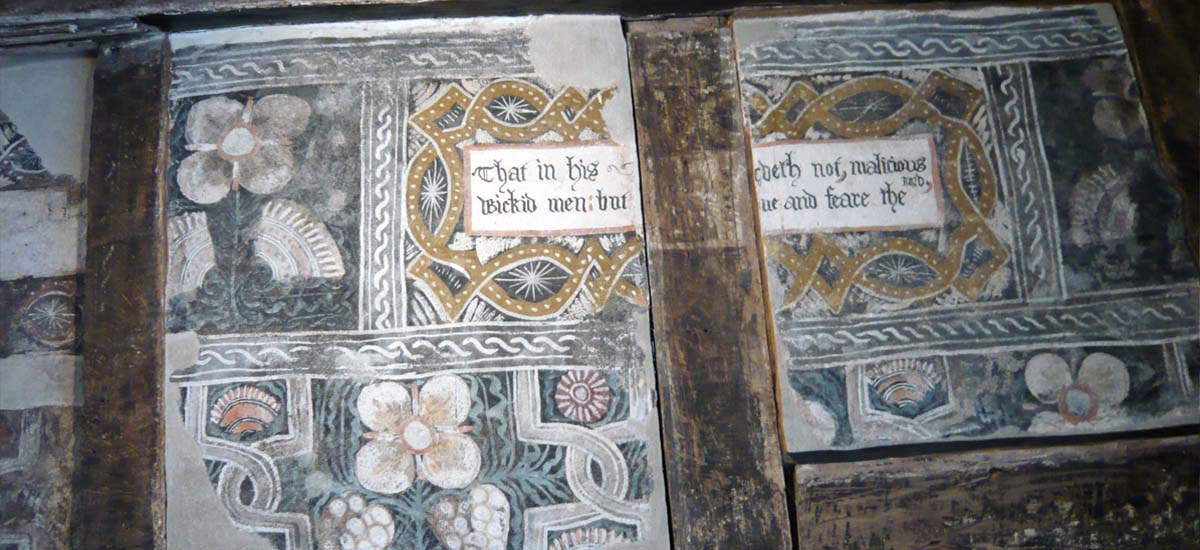

Elizabethan Wall Painting

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries homeowners employed local craftsmen to brightly decorate their homes with beautiful hand painted designs. As fashions and society changed most of these paintings were lost but fortunately some survive today, often discovered during renovations or behind panelling in vernacular buildings. Thus we are reminded of the colourful, exuberant tastes of our Elizabethan ancestors.

As more and more of these wall-paintings are discovered the evidence suggests that the fashion was more in favour of decoration than not. Indeed our current vogue for exposing beams and brickwork in old buildings would appear to our distant cousins to be as strange as exposing concrete lintels and breeze blocks is to us. By the middle of the 17th century the paintings almost entirely disappeared, frowned upon by the puritans as 'sins of the flesh'. And so it remained until the middle of the nineteenth century when we saw a Gothic revival with designers such as William Morris reviving the early designs, now in the form of wallpaper.

Significance and format of the wall paintings

Beyond the basic human desire for decoration, these wall paintings often served a more significant purpose. Much could be communicated by your choice of design; you could convey your intellect, education and wealth, celebrate an important event or a move up the social scale or assert a religious or moral stance.

Over the years these designs have been classified into types such as figurative (family portraits, biblical or mythological stories etc), floral, renaissance, geometric, imitation panelling and others. During the height of their popularity they covered entire walls in a composition that typically consisted of a frieze running across the top, a main panel called the fill, and a dado that ran across the bottom.

The Artists

In and around London the Painter Stainers Guild had jurisdiction over the craft of painting in oils and water-based paints. Beyond London there are few records of artists dedicated to the craft. There is some mystery as to who exactly carried out the decoration but it seems to have been done by bricklayers, carpenters, embroiderers, plumbers, glaziers and many other craftsmen with the plasterers seemingly cornering the market. This range of skills helps to explain some of the sources for designs as each craftsman would have their own pattern books and reference material to draw upon. For example, the embroiderers knew the famous pattern book A Schole-house for the Needle published in 1632 by Richard Shorlyker and some wall paintings are certainly reminiscent of blackwork embroidery.

Paint

Paint was made by mixing dry pigments into size made from plants, fish, animal bone and skin. This was painted onto lime plastered walls, wood, stone and even brickwork, often in a continuous pattern as if to obliterate these architectural elements.

Painted decoration was often intended to impress and display the wealth and social standing of the owner. The choice of colour could reflect this as clear, bright, stable colours were expensive to achieve and were used widely in royal palaces. Hence we see some schemes that to our eyes are extremely garish but that would have been admired and respected in their time. The most common pigments used were lime white, lamp black, red and yellow ochres and red lead.

Elizabethan Painted Cloths ~ an introduction

Painted cloths are one of the rarest and least studied forms of textile art as so few survive today and yet inventories and wills are testament to how common they were from the Middle Ages through to the 17th century. Even Henry VIII had several "stayned cloths" listed in his inventories. What started out as a fashionable and affordable substitute for tapestry was eventually relegated to the domain of theatrical scenery as fashions changed along with developments in manufacturing techniques and overseas trade (e.g. wall papers and printed cotton calicoes from India).

From their beginnings as courtly hallings in Medieval England they reached the Tudor manor house and eventually, in the mid-16th century, became affordable to yeomen and merchants who prized them for their farms and town houses. Here their function went beyond decoration as they served to keep out draughts and to disguise uneven walls.

16th and 17th century painted cloths were known as painted or stained cloths (or water-works). They were largely produced by the Painters-Stainers Company who formed in 1502 (the painters and the stainers are recorded as separate fraternities in London from the 13th century). By the 17th century imported cloths were overwhelming English ones, with many coming from the Netherlands and Germany.

Techniques:

The painter-stainers used a glue tempera whereby earth pigments were bound with animal size and sometimes limewater. This produced an inexpensive, impermanent paint suitable for decorative purposes. They produced hangings on linen but also hemp, wool and silk. For water-works less size was used in the paint mix resulting in a softer cloth more suitable for gathered draperies, valances, curtains etc. For a smoother and stiffer cloth more size was added to prime the fabric, filling the weave more substantially and allowing for a smoother surface on which to paint details.

The subject matter for painted cloths designs seems to have been along the same lines as that for wall paintings. There was probably more focus on imitation tapestry designs as the weave of the cloth would add to the illusion. In the 17th century we start seeing many forest scenes known as verdures being imported from Germany. These versatile scenes had a standardised background landscape of trees, hills, buildings etc with interchangeable narratives such as a hunting scene, mythological tale or, as at Owlpen Manor in Gloucestershire, the biblical story of the Joseph and his brothers.

Conclusion:

This is only a very brief and simplified overview of what is a truly fascinating area of research and discovery. My aim has been to give some insight into the kind of work I’ve been doing since 1996 and why I feel so passionately about reviving this vital episode in our decorative development. To delve deeper into this subject I highly recommend the following books which are rich in images and information.

Recommended Further Reading:

Artisan Art: Varnacular Wall Paintings in the Welsh Marches 1550 - 1650

By Kathryn Davies, Logaston Press, 2008

Domestic Interiors: The British Tradition 1500 - 1850

By James Ayres, Yale University Press, 2003

All Manner of Murals: The History, Techniques and Conservation of Secular Wall Paintings

Edited by Robert Gowing and Robyn Pender, Archetype Publications Ltd. 2007

A detail from an Elizabethan wall painting in Sandwich, Kent